Improving operational efficiency in a small practice: Muthaiga Pediatrics

An overview of MIT students’ 2009 project to analyze and refine the daily operations and standard processes of a general pediatrics clinic in Nairobi, Kenya.

In the fall of 2009, a team of four MIT students applied to work with Muthaiga Pediatrics. The clinic’s head had set their goal: to make the most of Muthaiga Pediatrics’ existing resources so as to “provide a much higher level of medical care in a modern highly organized environment [and eventually to] transform the busy single pediatric practice into a growing clinic chain with a strong brand.” Between them, Joshua Gottlieb (of MIT’s BEP program, which combined Health Sciences and Technology with a Sloan MBA), Michael Irwin (MBA), Michelle Bernardini (MBA), and Tessa Strong (MBA) had some 20 years of work experience, and combined skills in strategy, business development, fundraising, operations, process improvement, distribution, project management, training, and mentorship.

About the organization

Muthaiga Pediatrics (also known as Dr. Nesbitt & Associates Clinic) is a private, general pediatrics clinic located on the grounds of a prestigious hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. The clinic, run by Dr. Sidney Nesbitt, had six staff members and saw 25 to 30 patients a day. The clinic’s mission was to deliver the highest quality pediatric care by providing a personalized, family-friendly experience.

Operations as a focus area

Muthaiga’s project proved a great opportunity for the students to develop their skills and experience in the important domain of operations, internal processes, and logistics. Operations form one of GlobalHealth Lab’s focus areas. As in other operations projects, in this case students worked with the organization to analyze and refine its daily operations and standard processes in order to improve efficiency and effectiveness of the care it provides.

Once on the ground in Kenya, students built organizational charts, wrote job descriptions, mapped process flow charts, standardized forms, and created tools in order to streamline Muthaiga’s operational processes and minimize patient wait time.

The remainder of this document takes you through GlobalHealth Lab’s Muthaiga Pediatrics project step by step, sharing the tools and methods that the students applied to address Dr. Nesbitt’s needs. This guide is adapted directly from the work of the student team. Along the way we’ll highlight key factors that contributed to the project’s success. The work was divided into four phases.

Phase I: Setting the plans

The team’s first task was to define a project statement that would focus their work in the coming months. In the early stages of any improvement project, a clear statement of project goals is instrumental in framing the work and task design; later, such a statement can prove useful in preventing project scope from creeping up. The team designed and ran their own brainstorming session and held multiple conversations with Dr. Nesbitt, yielding the following guidance:

“The MIT team will investigate best practices and successful ‘Brand Promise Continuity’ at other ‘gold standard’ clinics both locally and internationally. In particular, the team will focus on resource staffing, patient processing, and standard care procedures. Additionally the team will brainstorm and investigate other potential mechanisms for improving clinic efficiency, including expanding the practice by incorporating other pediatric sub-specialties on location for referrals, and developing a culture which better ‘incentivizes’ efficiency in the staff.”

The team also developed a high level project work plan (doc) outlining the work the team would undertake during the semester from the MIT campus and an initial plan for the work that would be completed on site in Nairobi.

Phase II: Learning from successful practices

The team spent weeks conducting research at MIT, drawing on a wealth of external and internal resources. Initial library and internet research provided a basic framework for understanding clinical practices and ideas for how to organize their study of the clinic’s practice. They turned to journals, studies, and guides and focused on three main sources: the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Entrepreneurs Resource, and Pediatric Clinics of North America. Equipped with this initial framework, the students then gathered ideas for how to both assess and organize clinical practice in focal areas. Interviews with practitioners in successful U.S. pediatric clinics gave the team ideas for best practices and insights against which the team could analyze and adapt these practices to the unique environment, culture, staff, and patient demographics in Kenya.

The output of this was an interim report (doc) and a portfolio of third-party materials consisting of useful checklists and standard operating manuals for pediatric clinics.

Phase III: Contextualizing, assessing, and implementing on site

In January 2010, the team traveled to Nairobi to spend three weeks working intensively alongside Dr. Nesbitt and his staff. They had designed a full day of activities for their first day on site, meeting every staff member individually, learning about their work and each person’s training and background, and surfacing their ideas, concerns, and suggestions. Students asked staff for their observations of inefficiencies affecting both their work and patient care. Meeting all relevant stakeholders on the first day and understanding the role each would play in the project proved immensely useful as it allowed the team to build relationships with the staff, understand their point of view and share the team’s objectives for the coming weeks.

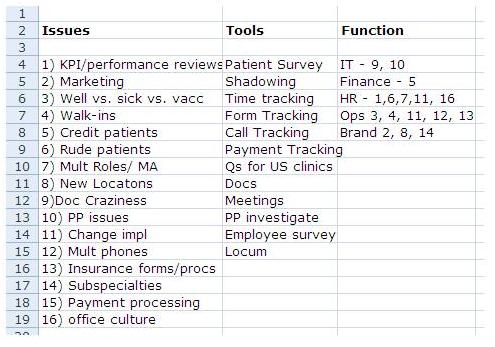

The team used the morning of their second day on site to discuss what they’d learned and to develop a process for addressing the issues identified by the staff. They outlined all the issues and defined the tools (e.g. patient survey, staff shadowing, data collection, etc.) that they would use to gain more information on each of the problems. They also created a project plan (jpeg) of activities they would undertake in the following weeks.

Collecting and analyzing data

Once the project plan was agreed upon, the team set out to methodically collect data that would inform their recommendations in three core areas: updating staff job descriptions and checklists, improving clinical operational and patient wait times, and creating a culture of improved effectiveness and collaboration.

- Working in pairs, students shadowed the clinic staff to understand the tasks and responsibilities required for each role. They drew on this research to create a set of job descriptions (pdf) and daily checklists (pdf) for staff to use while working to ensure that their tasks were completed in a timely manner and in the most efficient sequence.

- During the initial job shadowing, the team observed that reception was a key bottleneck in the overall clinic operations. The team created a reception tracking timesheet (xls) to record call volume, timing, duration, purpose of the calls, and who was answering the calls. One team member spent a full day stationed behind the reception desk, observing and recording all incoming phone calls. This data informed recommendations for improving service during peak morning hours.

- The team created an optional, anonymous patient survey (doc), that they used to elicit patient preferences for areas such as appointment scheduling, and the availability of credit and acceptance of insurance. This data informed recommendations for setting policies at the cashier and establishing scheduling guidelines at reception.

- The team monitored patient waiting time during visits. They used this data to create a model. First, the patient flow process was divided into distinct “stations”, including reception, triage, doctor consult, vaccinations, and cashier. The team created a tracking model (xls) for recording time spent at each station as well as idle time in the process. To track patient time, one person maintained a master spreadsheet and monitored the waiting room and reception area, and another team member, based in the doctor’s office, monitored triage/vaccination, and doctor consultations.

- The team created a set of flow charts (pdf) by station, to track from start to finish the process a patient faced at each step in the clinic visit process, as well as the decisions that the staff members were required to make at each step. A team member observed patient-staff interactions at the various stations (including nurse triage and doctor consultations), to understand the process flow throughout, and to see which steps might be extraneous or redundant and may be cut out or performed more efficiently.

- Lastly, the team created an employee survey (pdf) that was used to collect anonymous feedback on staff perceptions of how well the clinic was operating. Surveys were distributed to staff and a confidential folder was established to collect the completed forms. This informed recommendations for creating an improved culture of effectiveness and collaboration.

Testing the ideas and the process

Having completed data collection and analysis by the second week on-site, the team selected a subset of the proposed changes to implement. Their aim was to generate a set of small wins, so the initial changes were incremental but proved extremely informative. In collaboration with Dr. Nesbitt, each staff member undertook one change for a single day as a trial. The team explained the change individually to each staff member, making sure to emphasize the benefit such a change could have on their daily processes and free time during the day. For example, one small change was to improve the collection of patient information before an appointment, minimizing delays and errors in patient processing. When booking appointments, the staff at reception was asked to identify forms needed for that type of appointment and to direct the patient to the website or to send the form by email for the patient to complete. If the patient had no internet access, the forms were made ready on arrival and the patient was asked to come early to complete them. Another change was to establish a daily 15-minute morning check-in where the entire team could review and discuss the day’s plan and bring up any red-flag issues. Testing out a few changes helped both students and staff to develop a sense of the change management process at the clinic. It also helped test if the team had correctly assessed some of the observed problems.

Delivering the final presentation

After three weeks of intensive work in the Nairobi clinic, the team delivered a two-part final presentation (pdf). Part one presented the project background, process, and recommendations of the work on site to the entire clinic staff. The team’s goal was to ensure that every employee understood the purpose behind their work, the project’s specific goals, the team’s data collection and analysis, and how the proposed recommendations had come out of the process. The presentation included a reflection session in which each staff member assessed his or her experience with the change the students had proposed they implement. Both positive and negative evaluations and comments were sought. This segment encouraged communication between staff members and helped both the team and their host to appreciate the dynamics that emerge when working to change established organizational procedures.

To address some of the broader questions that Dr. Nesbitt had first asked, the team delivered part two of their final presentation to the clinic’s doctors, office manager, and accountant. The students had analyzed commercially-available medical records software, Peak Practice, and made recommendations for partnerships with subspecialists in the Nairobi area. They proposed a new organizational structure designed to enable potential clinic expansion. The team also presented results of the employee surveys they had designed and carried out.

Phase IV: Project outcomes

The next day, the students said their farewells to Dr. Nesbitt and his staff. They left Nairobi feeling they had accomplished quite a bit, having provided their host with what they anticipated was both a base for further improvements and a plan for going forward. The changes they had already helped to accomplish were, they hoped, just a taste of what would be possible.

Almost a year after the project was completed, the GlobalHealth Lab faculty team had the opportunity to catch up with Dr. Nesbitt to see how things had progressed. We learned that many of the team’s practical recommendations were still in place. The staff continued to meet daily to communicate the plan for the day and discuss outstanding issues, an activity Dr. Nesbitt especially valued for its team-building benefits. Reception continued to schedule patient visits by type, reserving time in the morning for “sick visits” and the afternoon for “well visits,” allowing the practice to better meet patient needs. The students’ survey of patient families had shown that only a small fraction valued credit services, which in turn enabled Dr. Nesbitt to eliminate his efforts to work with insurers and provide credit to patients. In addition, the process of the project itself resulted in an internal change in how problems were thought out and resolved. Dr. Nesbitt noted that by working closely with and observing the MIT students’ approaches, he and his team had updated their own approaches, beginning with analyzing issues more critically and drawing on data to inform decisions. Dr. Nesbitt also became more aware of his management style and, by his admission, became “more fluid and flexible” in interactions with his team.

Some recommendations were still a work in progress. Responding to feedback from the employee survey, the MIT team proposed monthly meetings with individual staff members for providing focused feedback on performance and responding to employee concerns. This recommendation had not yet been carried out when we last spoke, because of a lack of time: Dr. Nesbitt fills the role of both manager and pediatrician. Echoing a general shortage of professional service skill in Kenya, Dr. Nesbitt’s told us that his ongoing challenge to find a capable office manager that could handle some of the office management responsibilities, allowing him and his staff to focus on getting their own jobs done.

Sharing the experience beyond Cambridge and Muthaiga

There was a further benefit of the GlobalHealth Lab project—one nobody foresaw. In the Fall of 2010, Dr. Nesbitt was invited to present Muthaiga Pediatrics at the Office of the Future exhibit for the American Academy of Pediatrics by Dr. Gregg Alexander. Dr. Alexander, of Madison Pediatrics Inc., Ohio, is a doctor who calls himself “a grunt, in-the-trenches pediatrician” and directs the exhibit and is a member of the Professional Advisory Council for ModernMedicine.com. He had learned of Dr. Nesbitt via the MIT team: As part of their pre-visit research, the students spoke with him and several other leading practitioners. He met Dr. Nesbitt by email and then phone, and eventually in person. Dr Alexander wrote about what he learned in his blog on Health Information Technology, or HIT:

“Dr. Sidney Nesbitt…. is a pediatrician in Nairobi, Kenya. He is one of the ‘blessings’ I have been granted through my time in the HIT realm. He runs the Muthaiga Pediatrics Clinic located on the grounds of the Gertrude’s Children’s Hospital, a charitable trust founded over 70 years ago to help the children of East and Central Africa.

Sid’s working very hard to develop and employ advanced office design, practice management, and especially healthcare information technology techniques and tools at Muthaiga Pediatrics. His goal is to set a standard, an example that he can share with physicians all around East/Central Africa. He even engaged the interest of MIT Sloan’s Global Health Delivery ‘G-Lab’ [the former name of GlobalHealth Lab] which worked with him for months helping him evaluate and deploy better business tools specific to the needs in Nairobi. I was lucky enough, along with the wonderful Drs. Dan Feiten of Denver and Larry Rosen of New Jersey (himself, an MIT alum) to consult with their project.

He is truly an inspiration for me and, I’ll wager, for many, many more folks around his native Kenya. He’s a joy with whom to talk and constant source of ‘what others are striving to do with far less resources and far greater challenges.’ He helps me remember what’s important.”

The following selection of materials created by the student team in collaboration with Muthaiga Pediatrics is available for download here (these are the same as those linked throughout the document above):

- project work plan described the goals for the project and breaks down responsibilities and final deliverables to be completed

- interim report was delivered by the MIT team to Muthaiga senior management upon their arrival onsite and outlines their research for the project to date

- project plan showed a timeline of activities to be undertaken onsite

- job descriptions, daily checklists, and reception tracking timesheet helped the team and the staff precisely define and focus on the tasks designated for each staff member and find bottlenecks in patient flow at reception

- tracking model and flow charts were used to record and organize the time patients spent waiting and being seen at each of a series of hospital stations during their visits, as well as the decisions the staff members were required to make at each step

- patient survey was administered to patients (by choice and with anonymity) to elicit preferences for areas such as appointment scheduling, and the availability of credit and acceptance of insurance

- employee survey was used to collect anonymous feedback on staff perceptions of how well the clinic was operating

- a two-part final presentation given at the end of the MIT team’s onsite work

Want to know more? Download the tools linked throughout this article and watch the Final Presentation Video Part I and Part II.

Was this article useful to you? Please give us feedback on how to improve sharing our work by leaving us a comment or e-mailing us at global.health.lab [at] mit.edu.